↓

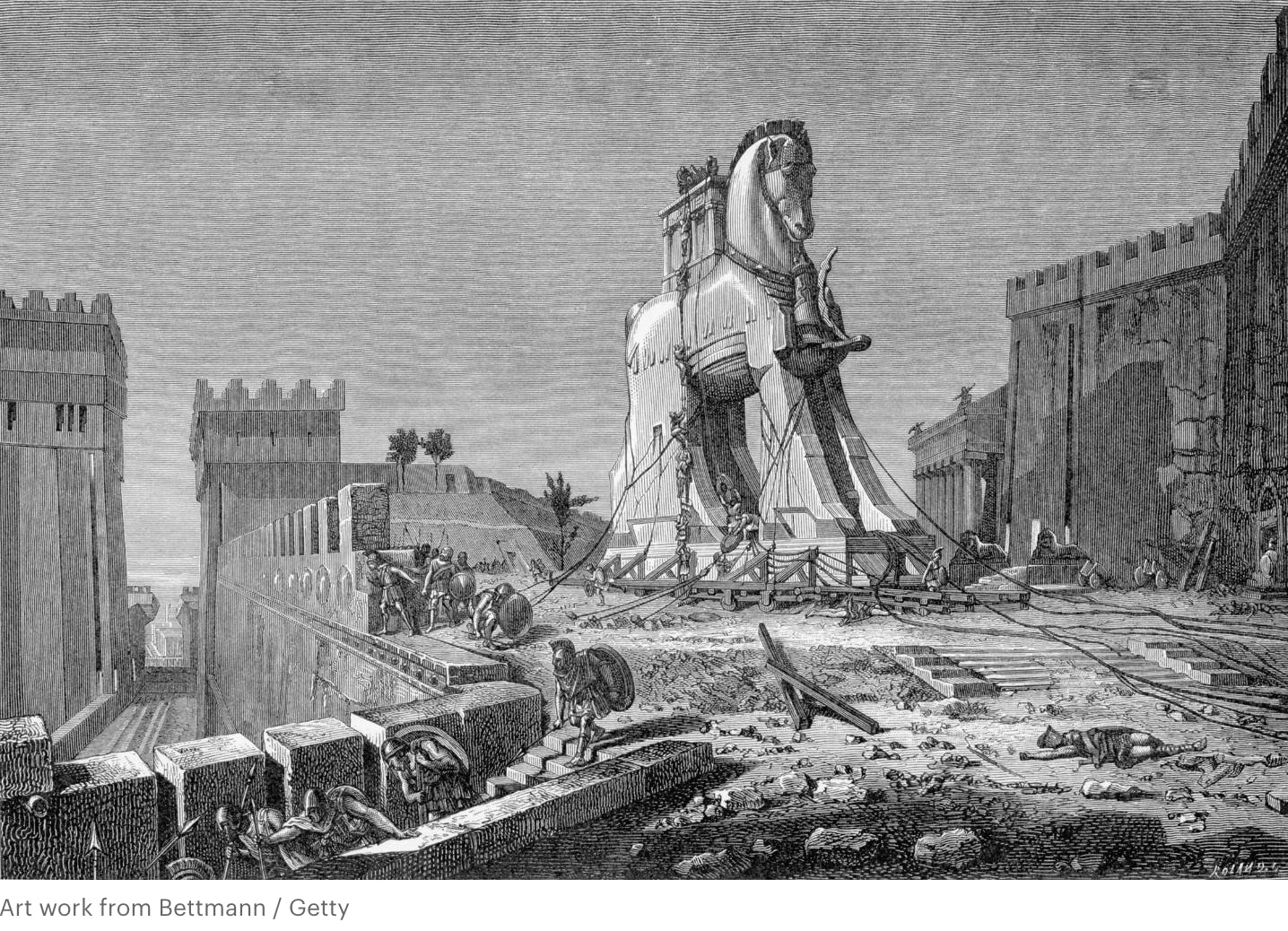

Virgil's tale is familiar:

“Pull the statue to her house”, they shout,

“and offer prayers to the goddess’s divinity.”

We breached the wall, and opened up the defences of the city.

All prepare themselves for the work and they set up wheels

allowing movement under its feet, and stretch hemp ropes

round its neck. That engine of fate mounts our walls

pregnant with armed men.

We know what happens next (spoiler alert).

Less mentioned: this maneuver ended the Greek's ten-year siege of Troy.

How could it take so long? Menelaus had listened to all of the advice of the day; he possessed the greatest war machine of the Aegean, led by a rockstar team including Agamemnon, Achilles (!), and even the fortuitously-named-for-our-metaphor Ajax.

But all it earned the Greeks was a false sense of progress, as that Trojan Hector would emerge from the city (!) ... only to fight instead of surrendering.

Let's call this ten years the "add features until they love it!" phase of searching for P/M-fit.

Honey Badger Market Don't Care

Before Google was a single search input field it was an appliance — yes, a physical device, you'd install to crawl your corporate intranet and make it searchable.

Before Segment was a tidy little event router snippet of JS, it was an entire analytics platform that needed a way for data to be easily routed to it.

Before Instagram was a feed of filtered photos, it was Burbn, a location-based iPhone app that "let users check in at particular locations, make plans for future check-ins, earn points for hanging out with friends, and post pictures of the meet-ups."

These companies had armed themselves with so much value it hurts. Why didn't the market respond?! Who didn't want an analytics platform? Who didn't want to have a shiny golden device that crawls their intranet, provisions a portal, and makes it all searchable? Who didn't want to have an app that lets you check in, earn points, and post pictures?

Everyone, apparently.

These things were just too big. Each of these early product teams went post-fit roadmap in their pre-fit world.

Wedging In

On day zero, your product has no surface. This is a problem because without some UI you can't learn anything.

So you start building to fix the problem; but now you have a different problem, which only the best product teams discuss, let alone decide: which things are worth keeping? And how do we know?

Let's do a quick reality check: where are we now? Are we a market leader with a validated roadmap? Quite the opposite: we're still standing outside the market with very little validation.

Fortunately, there's advice for this stage: to break into the market we need a wedge. But what is a wedge, exactly?

Is our company the wedge? Maybe it's our product? Or perhaps the wedge is our strategy? Yes! That's it, a strategic wedge. So good.

No. No, no. Stop it. The wedge is not your company, your product, or your strategy. The wedge is a shape that's able to enter the market because the market recognizes it, allows it in, and (and very importantly) because it fits.

And this shape, or rather, the negative of this shape, is decided by the market's defenses, not you. Yes, Odysseus built the horse, but the Trojans provided the spec: it needed to have an appealing shape (a war horse), it needed have a plausible reason for existing (it was ostensibly an offering to Athena that would make Troy invincible), it needed to fit their entrance (sorry, we can't rebuild our main gate to accept this thing), and, if it's not too much to ask: preferably all in an easy-to-drag structure (wheels and dangling ropes included)?

What About Us?

It's not lost on me as a founder that none of these wedge specifications have anything to do with your motivations as a business: your vision, your strategy, your desire to win the market.

Yet if you're going to realize any of these, you must accept that they are all subservient to the shape the wedge needs to be in order to successfully enter the consciousness of your buyer, i.e. positioning.

Selfishly, yes, we want to pack as many features as we can into this wedge, so that when it opens on the other side, the market is ours for the taking: "Wow, this product is so rich! It's so deep! A bottomless well of value! What else can they do for me?"

But that's all after fit. Until then, and all the way until the city gate, every feature you draw attention to is a tax on clarity and a risk that you won't be able to enter. You're just too much, too soon.

Instead, your product strategy before fit should resemble an hourglass: build, test, reduce, be willing to package it all into a wedge that belies your vision, then expand.

It's your only chance.